Like doo-wop, the earliest era of rap was full of groups and ensembles, many with numbers in their name, who were known for routines in which they passed lyrics between each member and often broke out into song.

From it's inception forward, there have been various moments that hip-hop has paid tribute to it's street corner predecessor, often directly through music or lyrical content.

On a broader scale, doo-wop could be said to be referenced in hip-hop simply through a certain style or flair that was passed down, especially in the beginning.

We went from doo-woppin' to what now?

When early rap acts like the Furious Five or the Fearless Four rhyme and go between individual and synchronous recitations of lyrics, I certainly argue it is reminiscent of what one hears harmony wise from Dion and The Belmonts on “I Wonder Why” or the Valentines on “Lily Maybelle.”

Still, based on the young age of many hip-hop artists in the ‘70s, I believe this connection is more so that hip-hop’s influences are in the lineage of doo-wop, rather than being directly connected.

In the “Underground to the Mainstream” episode of the docuseries Hip-Hop Evolution (2016), directed by Darby Wheeler, DJ Grand Wizzard Theodore of the Fantastic Five explained that his group’s harmonized routines and choreography were inspired by the Jackson 5, the preeminent youth vocal group in the early ‘70s when hip-hop was being developed, by many kids who were Jackson 5 fans.

The Jackson 5 are not a doo-wop group, but they are descendants of that era, in some cases biologically.

Before his kids were a singing group, Joe Jackson had been affiliated with and tried to sing in a group with Thornton James “Pookie” Hudson and Billy Shelton, who had become friends in church choir and formed their group the Three Bees in the late ‘40s with the addition of Calvin Fossett, a classmate from Gary Roosevelt High School.

According to Jeff Harrell’s 2014 article on the group for the South Bend Tribune, by 1952, Thornton Hudson had reworked and expanded this line up into what would become the Spaniels.

The Spaniels are perhaps best known for 1954’s “Goodnite, Sweetheart, Goodnite,” famously sung by Sha Na Na as the closer for their variety show in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s.

Outside of group routines, references to doo-wop can be seen in the street talk style of certain solo rappers in the same era.

Chief Rocker Busy Bee Starski, a legendary MC known for his arrogant showmanship and call and response routines, used nonsense syllable lyrics associated with doo-wop in his performances.

Specifically, Busy Bee would say “ba-bidda-ba-ba-dang-ga-dang-digga-digga,” which was mocked by Kool Moe Dee in their infamous battle at Harlem World during a MC contest held for the Christmas holiday in 1981. The battle is also called an ambush since Busy Bee didn’t know Moe Dee would diss him.

I am not sure of Busy Bee’s direct inspiration in using these nonsense syllables, but to my knowledge one of the most popular sources of the phrase he says are the Marcels, initially formed in Pittsburgh, who left a mark on doo-wop with their 1961 hit rendition of “Blue Moon.”

When the Marcels covered “Blue Moon,” it was an already well-known and frequently covered song, originating in the 1930s as one of many collaborations of composer Richard Rodgers and song lyricist Lorenz Hart.

The bass voice for the Marcels, Fred Johnson, performs a string of repetitive sounds in the song’s intro and throughout, which to simplify basically reads as “Ba-bomma-bom-fa-dang-ga-dang-dang-fa-ding-ga-dong-ding.”

The opening bass vocal and overall structure the Marcels used for the song was inspired by the Collegians' "Zoom Zoom Zoom" from 1958, released on Winley Records and co-written by Paul Winley, who I discussed in another article.

In any case, this version of "Blue Moon" is famous, featuring one of the most famous nonsense syllable routines in doo-wop, perhaps best known by later generations for playing at the abrupt end of John Landis’ An American Werewolf in London (1981).

Melle Mel references these same “ba-bidda-ba” nonsense syllable lyrics in the first verse of the Furious Five’s “Step Off" from 1984. Specifically, Melle Mel says, “Before my reign, it was the same old same, 'to the baw-bidda-baw,’ that street talk game.”

Basically, Melle Mel made the point that he, as a pioneer of the modern form of rapping, elevated rap from its previous position in the streets. This suggests that “baw-bidda-baw” and similar phrases were standard things to say when rhyming or singing on the street back in the day, similar to when people would play the dozens or recite a toast like “Stagger Lee.”

Seeing as doo-wop is associated with the street corner, I think it makes sense that Melle Mel would mention aspects of the genre’s vocal palette as influencing street lingo when he was young. The Marcels’ version of “Blue Moon” had also come out in Melle Mel's birth year.

Outside the influence doo-wop may have had on rap lyricism, there were some rappers that even more directly channeled the essence of bygone vocal harmony groups.

Most notably is probably the Force M.D.’s, originally DJ Dr. Rock and the Force M.C.’s, a vocal harmony and rap group from Staten Island, initially formed in 1981 as explained in JayQuan The Hip Hop Historian’s video on the group for YouTube, based on interviews he conducted with past members.

The Force M.D.’s consists of many relatives, in part because the group basically resulted from the original roster of the Force M.C.'s combining with a singing family group called the Fantastic L.D.'s.

“L.D.” stood for the family names of “Lundy” and “Daniels,” including the Lundy brothers Stevie D, Rodney (or Khalil), and T.C.D. (or Antoine), and their uncle Jessie Lee Daniels. Stevie D was a member in both groups before they merged.

While the L.D.’s were known to famously sing on the Staten Island Ferry, the Force M.C.’s, with Dr. Rock as their DJ, toured the live circuit in New York City, battling with other rap acts. They were also featured on WHBI-FM 105.9 on the radio show hosted by the World’s Famous Supreme Team of Sedivine the Mastermind and Just Allah the Superstar.

Another pioneering hip-hop radio DJ, Mr. Magic, eventually learned of the Force M.C.’s, and through him they became known to Tom Silverman, the founder of Tommy Boy Records, who the group signed with I believe in 1984.

Tom Silverman was responsible for switching the group’s name to the Force M.D.’s, the acronym standing for “Musical Diversity,” to better advertise that they could both rap and sing.

Another decision that was apparently Silverman’s was to outfit the group in various sweaters featuring the letter “F,” in reference to the sweaters worn by Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers on the cover of their 1956 debut album, which were adorned with the letter “T."

The Force M.D.’s can be seen wearing these sweaters on the cover of their debut album Love Letters (1984), in their performance of “Let Me Love You” at Mr. Magic’s birthday party in 1984, or in their performance of “Itchin’ for a Scratch,” in Rappin’ (1985), directed by Joel Silberg, who also directed Breakin’ (1984).

The Force M.D.'s quickly left this look behind, sporting a more contemporary style on the cover of their next album, Chillin' (1985).

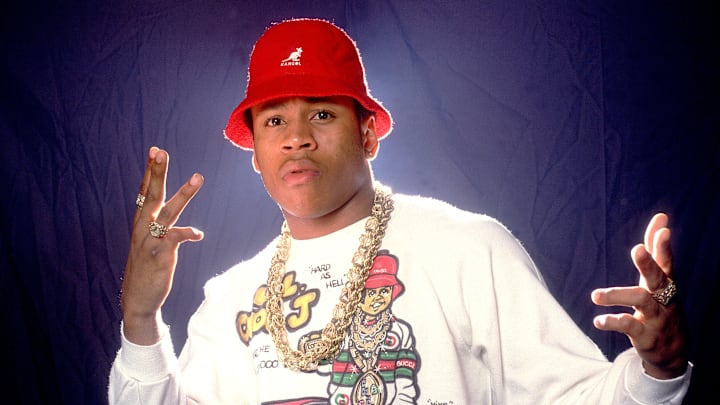

One of my favorite times hip-hop paid homage to doo-wop was in LL Cool J's track named "The Do Wop," which I believe references the genre along with the popular hip hop dance at the time, often associated with B-Fat's 1986 song "Woppit."

"The Do Wop" is the last song on LL Cool J's sophomore album, Bigger and Deffer (1987), followed by the skit "On The Ill Tip." In it, LL recounts his dream of the perfect day, featuring multiple romantic encounters interspersed with making bank from performing and bragging about his skills.

The reference to doo-wop lies not only in the title but also the production for this track, which loops the opening seconds of the Moonglows' "Over and Over Again" from 1956.

The album's production was largely courtesy of the West Coast production team the L.A. Posse, specifically Darryl Pierce, Dwayne Simon, and Bobby Ervin or “DJ Bobcat,” who became one of LL's DJs.

DJ Pooh was another member of the L.A. Posse involved in the album, having production credits on “The Bristol Hotel” and “.357 - Break It On Down," as well as possibly being one of LL's allies who helps him defeat the mob in the video for "I'm Bad," the album opener that references the wop dance in the first verse.

"The Do Wop" is a foundational hip-hop song for myself, and I am still curious about the sample choice.

The use of a sample from the rock and roll era reminds me of how Def Jam was marketing LL in relation to rock during that time, which they also did for their other acts like Public Enemy and the Beastie Boys, who had been a punk band in the past.

Like their Rush Artist Management peers Run-DMC, who redid "Walk This Way" with Aerosmith in 1986, Def Jam's rappers not only sampled rock but were advertised as identifying with it, or its hardcore essence, particularly in efforts to gain a young mainstream white audience.

Def Jam was advertised as circumventing the expected norms, not just of rap, but more importantly of rock and American popular music, signaling to white kids that rap was something different yet familiar, sampling history but delivering it with a hardcore rawness.

I am curious if this marketing scheme focused on subverting or reframing the standards of pop music informed the sampling on Bigger and Deffer. For example, the celebratory DJ track “Go Cut Creator Go,” lyrically interpolates both Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode” and "Rock Around the Clock" by Bill Haley & His Comets. Berry’s famous boogie woogie inspired guitar riff is directly sampled, specifically from "Roll Over Beethoven."

Outside of sampling rock and roll, LL Cool J's image as a rapper was marketed in other ways that were parallel to artists of that era, particularly in film. Like his performance of "I Can't Live Without My Radio" in Krush Groove (1985), directed by Michael Schultz, the Moonglows performed the song sampled for "The Do Wop" in a film that promoted them.

The Moonglows performed "Over and Over Again" and "I Knew From The Start" in the 1956 film Rock, Rock, Rock!, directed by Will Price. These songs were released as a single that same year, I believe in direct connection to the film.

Both songs featured on the soundtrack as well, released on the Chicago based Chess Records, which only featured the Moonglows, Flamingos, and Chuck Berry, all Chess artists at the time. Berry's "Roll Over Beethoven" is also on this record, and since that song was also sampled on Bigger and Deffer for "Go Cut Creator Go," it is probable that the L.A. Posse had the Rock, Rock, Rock! soundtrack in their record collection.

Like Krush Groove (1985) or Beat Street (1984) advertised hip-hop in the '80s, Rock, Rock, Rock! was one of a host of films of it's era that were essentially made to showcase rock and roll artists to white teenagers, sometimes involving a plot focused on young love.

Other films like this include Jamboree (1957), directed by Roy Lockwood and co-written by Milton Subotsky, who was a co-writer on Rock, Rock, Rock! along with Phyllis Coe. These films featured black and white artists such as LaVern Baker or Buddy Knox, as well as radio personalities like Jocko Henderson and Dick Clark in the case of Jamboree.

The radio personality heading Rock, Rock, Rock! was the legendary Alan Freed, who hosted a television program in the film that acted as the setting to see many of the performances.

As stated in radio DJ Jerry "The Geator" Blavat's article on the Moonglows for their induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2000, Alan Freed briefly managed and recorded the group on his label Champagne Records in the early '50s.

This was back when they were named the Crazy Sounds and based in Cleveland, where Freed worked for the radio station WJW. Freed dubbed them the “Moonglows” in relation to his nickname “Moondog,” which referenced his radio show the “Moondog Rock and Roll Party,” and was used for his Moondog Coronation Ball, a pioneering rock and roll concert held at the Cleveland Arena in the spring of 1952.

In short, I believe Def Jam in part wanted to market LL Cool J as an edgier update to rock and roll acts like Chuck Berry, and even the Moonglows. In this context, to sample the Moonglows on his album is fitting considering that doo-wop was and still is linked and marketed under the umbrella of rock and roll, as well as rhythm and blues.

Aside from what I consider an interesting example in "The Do Wop," these are only a few times I remembered when hip-hop referenced doo-wop, though there are many more, both in these eras and up until today.