Within the continuous additions to and retellings of music history, a genre such as hip-hop is usually caught within efforts to categorize and explain its origins, which happened largely outside of the music industry, and it began to enter in the late '70s.

Now that rap is so visible and popular within the industry, a constant point of interest relates to the origin of rapping. While many people enter into this discussion to find a concrete individual or place, I tend to feel that a retrospective need to give a very clean and concise starting point for rap to create an accessible narrative doesn't fully do justice to the rich cultural community that rapping and rhythmic talking emerged from, especially within the black diaspora.

This article certainly won't be able to give a substantive answer to this question, either. However, what it may be able to do is show that understanding the source of rap within hip-hop can be better approached if one removes any attempt at finding an easily defined answer to hold on to, and instead embraces the complexity.

Where did you get that rap from?

To explain my stance on the question of rap's origins very quickly, I believe that the most persistent elements of rap music, which build the history of the genre, are shared between various artists. Rather than focus purely on individual innovation, which is very important, room must be made to understand how the community innovates itself.

For example, there has been much discussion around how rapping started within the early era of hip-hop in the '70s. When people tell the story of DJ Kool Herc's early jams, there is often a mention of his understanding of Jamaican sound systems and toasting, having been born in Kingston.

JayQuan the Hip-Hop Historian's video on the "Golden Era" of hip-hop gives a great breakdown of this, explaining that Herc would toast, or speak in a sometimes rhythmic way, over break beats.

To give a quick example of this style of toasting, "This Station Rule the Nation," I believe from 1970, is a song featuring the pioneering talents of U-Roy, who toasts over the backing track, or "version," of "Love Is Not A Gamble," a song by the rocksteady group the Techniques, I believe from 1967.

The backing or rhythm tracks from pre-existing songs are also often referred to as "riddims" in Jamaica. The Stalag 17 riddim, originating from Ansel Collins' 1973 instrumental track, has been famously toasted over by Sister Nancy and Tenor Saw among many others to this day. Riddims are an endless source of music for various generations of artists to create their own songs, similar to how the same break beats would be used to rap over by early hip-hop artists.

As explained in Darby Wheeler and Rodrigo Bascunan's docuseries Hip-Hop Evolution (2016), Kool Herc's sound system not only amplified the bass in the music, but also could put an echo on his voice, similar to U-Roy's voice on songs such as "This Station Rule the Nation," as well as early examples of dub music in the era from engineers and producers like King Tubby and Lee "Scratch" Perry.

In a format certainly connected to Jamaican toasting, Herc and others like MC Coke La Rock were calling out and speaking over the break beats, sometimes just to give shout-outs or announcements, like saying someone's car was double-parked.

Over time, this evolved into MCs such as La Rock more purposefully getting on the microphone to say rhymes to the beats Herc played. From here, the early generation of rappers grew, or at least that is how the story usually goes in this context.

Focusing on these early parties in the Bronx is a very important perspective to have in order to understand the role of the MCs who were around Kool Herc in the beginning. However, I always find myself wanting to know more about how exactly the rhyming part began.

The story explains that the people at Herc's parties evolved into rhyming and rapping, but still doesn't fully explain how they, and especially those who closely followed within this era, developed what exactly they were rapping.

While I do not have a concrete answer regarding Kool Herc's early parties in the Bronx, my most educated guess regarding the origins of rap is that rapping did not simply evolve from within the hip-hop scene, but was instead adapted to the growing hip-hop scene based on things that had already been happening around it.

For example, many of the DJs and MCs within New York's earliest era of hip-hop in the '70s speak about the influence of radio DJs such as Frankie Crocker, Hank Spann, and Gary Byrd, each of whom utilized rhyming and rhythmic talk while on the air.

This was known as "rapping," or as "having a rap," and was a style passed down through other legendary DJs, such as Philadelphia's Douglas "Jocko" Henderson, who also worked in New York and Baltimore, the latter being his birthplace.

Within the history of black music, the cool rap style of these radio DJs had clear ties to the gift of gab and jive talk rhymes of jump blues and early rhythm and blues artists like Louis Jordan, as well as jazz icons such as Cab Calloway, who famously authored or at least had his name and persona attached to multiple jive dictionaries published since I believe the late 1930s.

As discussed in my article on nostalgic rap songs, black comedians such as Pigmeat Markham and Rudy Ray Moore were also known for having their own raps.

While Kool Herc brought influences from the Jamaican tradition of toasting, Moore often performed African American toasts, such as "Shine and the Titanic," sometimes referred to as "jail toasts" because of their prevalence, at least in the early to mid-20th century, as a spoken word subculture amongst incarcerated black men.

In a 2014 interview with Mark Skillz for Medium, the highly influential New York based DJ Hollywood, who had a background as a singer and sought to mesh that with the styles he heard from Frankie Crocker, Hank Spann, and Rudy Ray Moore, explains that one of his first rhymes in 1975 was basically a reworking of Isaac Hayes' lyrics on "Good Love 6-9969" from Black Moses (1971), which he recited over the breakdown at the end of "Love Is The Message" by MFSB (Mother Father Sister Brother).

In relation to both black music and comedy in the '70s, the sounds of the black poetry of the Black Power era, which groups such as the Watts Prophets referred to as "rapping," would also be influential on what early hip-hoppers, and certainly their successors, thought to say once they obtained a microphone.

Poets and activists of that era, such as Jesse Jackson, were influential not only for lyrical content but also as examples of how to energize a crowd and gain their participation. Jackson's "I am! Somebody" routine can be heard being directly lifted by the likes of Chief Rocker Busy Bee when he does call and response with the crowd.

Busy Bee also patterned his boastful persona after Muhammad Ali and utilized his famous rhyming routines with cornerman Drew Bundini Brown.

Jalal Mansur Nuriddin of the Last Poets, a black poetry group who have been referenced countless times in hip-hop, released his own project in 1973 entitled Hustlers Convention, using the moniker of Lightnin' Rod. This narrative album was created in the style of the jail toasts performed by comedians such as Rudy Ray Moore and pimps such as Iceberg Slim.

Hustlers Convention has been referenced by multiple generations of hip-hop MCs, such as Grandmaster Melle Mel and the Furious Five's "Hustlers Convention" song, the opener for their self-titled 1984 album.

It's basically a cover of "Sport," the first song on Hustlers Convention, which featured the instrumentation of Kool & The Gang, and was sampled by the Jungle Brothers and Q-Tip on 1988's "Black Is Black," a track on the Jungle Brothers' debut album Straight Out The Jungle.

Also in 1988, Ice-T, who was highly influenced by the toasts of figures like Iceberg Slim, as his name showcases, also referenced Hustlers Convention on his song "Soul on Ice," the last song before the outro on his sophomore album Power.

In short, I just wanted to give each of these examples basically as context to show in what ways rapping or earlier forms of rapping were already known within the black community in New York, and parts of the larger black diaspora, when hip-hop was beginning to form in the '70s.

While hip-hop was an extremely innovative space, its innovation had to, of course, develop from what already existed, which I believe is one of the genre's greatest strengths.

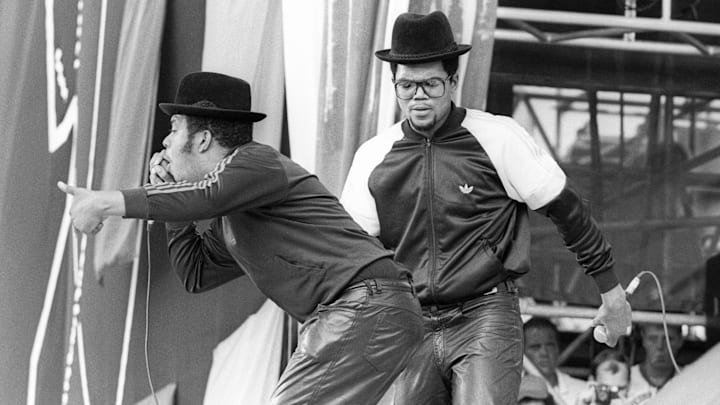

This system of influence being passed down through generations should also be counted as an innovation within hip-hop. To understand my point, one only needs to hear Run of Run-DMC say the first half of the group's name at the beginning of "Rock Box," as since the song's release in 1984, his voice has been referenced numerous times.

J Dilla sampled Run directly for "Runnin'" by the Pharcyde, while Redman vocally imitated it in the second verse of "Pick It Up."Jay-Z makes a similar reference near the start of the first verse of "Where I'm From."

In my opinion, more than the role of individuals, the community has been pivotal to how the act of rapping has passed down to the hip-hop generation, and I believe in some way will continue to be important for the generations yet to come, who will primarily have hip-hop to look for as the source of rapping in popular culture.