I am not a Deadhead. I saw the Grateful Dead four times in my life – once when they were accompanying Bob Dylan – and I was nowhere near as well versed in their music as my college roommate, whose self-imposed deadline for finishing his senior-year thesis was the start of the next Dead tour, or as my nephew, who plays in a Dead tribute band. Nonetheless, I always felt like I had a particular affinity for Bob Weir.

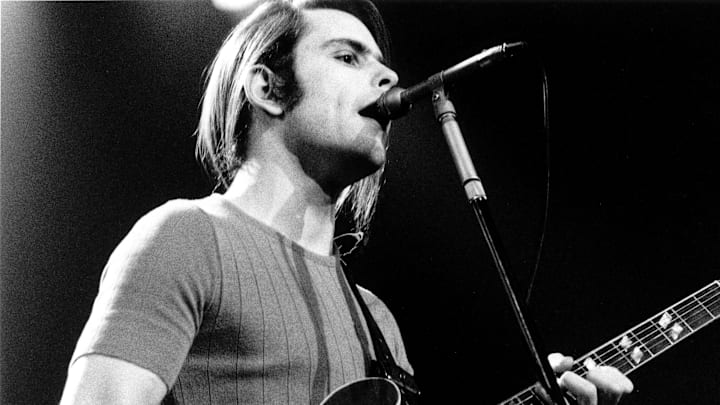

You see, I’m the youngest in a family of lots of boys. That’s the role that Weir, who died Saturday at the age of 78, had in his iconic band. He joined them when he was a teenager. His initial role – rhythm guitar and harmony vocals – was classic glue. In a band of strong personalities and divergent musical impulses, Bobby was the logical member to stand in the middle.

The lead guitarist never takes that role. Nor does the singer. In the Dead’s case, both those roles were filled by Jerry Garcia. The bass player is usually living in his own world. So it’s always the drummer – Ringo in the Beatles – or the rhythm guitarist – Ron Wood in the Stones – who kind of keeps the big personalities from killing each other.

But what happens when it turns out that the glue guy has a big personality and strong musical impulses on his own? That was Bob Weir.

Bob Weir, who emerged as the co-leader of the legendary Grateful Dead, dies at 78

Growing up, Weir suffered from dyslexia. As a result, he never thrived in school. He turned to music and became immersed in the early ‘60s scene in his hometown San Francisco. That’s where he met Garcia, five years his senior. They formed the Dead along with Phil Lesh on bass, Bill Kreutzmann on drums and Ron “Pigpen” McKernan on organ.

Lesh had a classical background while Pigpen was all about the blues. Jerry was enamored by bluegrass. It didn’t happen right away, but somehow they made it work. The earliest albums were middling affairs. Even at their best, the Dead were never a studio band. It was in live performance where they began to build the single most dedicated fanbase any modern musical act has ever known.

As they developed, Weir began to assume a more prominent role. By the time of their sensational double punch of 1970’s albums Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty, his spacy folk-rock impulses were reaching maturity.

He co-wrote and sang “Sugar Magnolia” and “Truckin’,” two of the band’s most beloved numbers. The latter was the band’s highest-charting song until 1987, though it failed to crack the top 40. 27 years after its release, “Truckin’” was classified as a national treasure by the Library of Congress. Weir was about to turn 23 when he recorded it.

If his earliest leanings were toward folk rock, like the rest of the band, Bob Weir began branching out throughout the ‘70s. Blues and jazz all swirled around in the prototypical rock jam band kettle and produced some spectacular music later in the decade.

“Estimated Prophet,” which kicked off 1977’s Terrapin Station had a funky blues vibe. “I Need a Miracle,” 1978’s “Shakedown Street,” was first-class swamp rock.

He wrote both those songs with long-time friend and collaborator John Perry Barlow. Weir had written “Sugar Magnolia” and "Truckin’” with the band’s primary lyricist Robert Hunter, but Hunter worked better with Garcia. So Weir wrote music and Barlow wrote the words on many of the band’s later songs. “Cassidy,” “Throwing Stones,” and “Mexicali Blues” is just a small sampling of their work together.

Weir was not without his detractors. There are actually some pretty intense debates as to how good a guitar player he was. I’m admittedly biased, but to me, he was among the very best rhythm players of the rock era. Bob Weir didn’t play “pretty.” I’m sure you can imagine what kind of clever nicknames his classmates came up with for a dyslexic kid named “Weir,” but he ended up playing weird chords in the best possible sense of the word.

Bob Dylan called his rhythm playing “strange” and ‘unpredictable” but marveled at how he always made it fit the song. Garcia called him unique. The word you’ll see often associated with the way Weir played rhythm guitar is “angular.” If you don’t know what that means, think of it this way. It is the opposite of smooth. The chords go in strange, unexpected places. Yet it still somehow works.

It would be wrong to say that Weir’s playing gave the Dead their unique sound. Every member brought his own perspective to the music The Dead morphed as band members came and went and each was integral to their sound. Jerry was the leader. But Bobby was a foundational piece. In a very important way, he did create something unique.

The deeper, nastier complaints about Bob Weir are not about his angular playing but about what he did after Garcia died in 1995. There are some diehard fans who felt Jerry’s death should have been the end. It wasn’t, largely because Bob Weir kept the Grateful Dead alive.

He became both creator and curator of one of America’s vital musical institutions. He played in a lot of Dead-adjacent projects over the last thirty years. If not everyone thought that was the right way to honor Jerry’s legacy, the millions and millions of fans who were entertained by Bob Weir’s bands over the last three decades would most likely disagree.

“My whole life is constantly trying to shove ten pounds of rats into a five-pound bag.” He told that to Brett Martin for an excellent 2019 profile in GQ Magazine entitled “King Weir.”

It’s a weird thing to say but that was Bob Weir. He saw things through his own eyes and heard them through his own ears, and somehow, over a very long and insanely productive career, the kid who kept flunking out of school as a youth, held together an American institution. He did it in the most unassuming way imaginable. If you’re the youngest in the group, you understand how that works.