He might have been too handsome for his own good. Or too smart. Too passionate. Those are all good things, of course, but at various points, they all probably had an adverse effect on the songwriting career of Kris Kristofferson. The drinking and womanizing were more self-inflicted wounds.

I was traveling – away from my computer – when news of Kristofferson’s death at age 88 broke. By the time I sat down to write about him, a mere thirty-six hours later, tributes had already poured in from many corners of the cultural universe. Country music performers weighed in most prominently.

That might have bewildered the younger Kristofferson, who arrived in Nashville at age 29 in 1966 with nothing more than scruffy good looks and a radical poet’s sense of lyrics. Unable to make it as a songwriter for a few years, he worked as a janitor in one of Nashville’s many music studios.

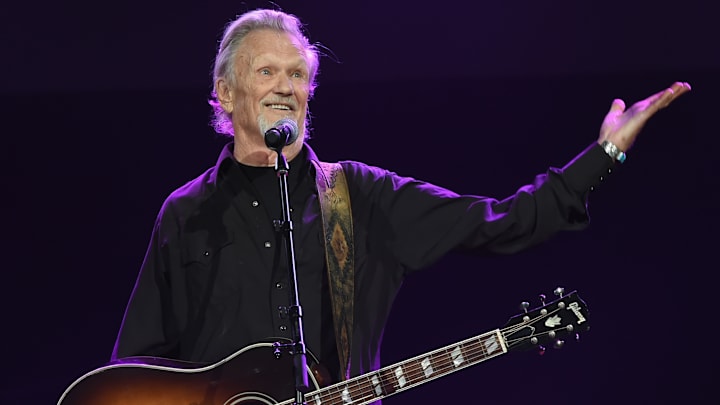

Kris Kristofferson was truly one of a kind

If you grew up when I did, in the 1970s, with more of an interest in rock & roll than in country music, Kris Kristofferson was something of a lightweight. He was eye candy in several very successful movies in that decade. It wasn’t that Kristofferson was a bad actor. He just wasn’t a good one. He had the natural performative charm that allowed him to be good in roles that suited his personality. He had wit and sex.

But he was untrained, and when called on to play nuance or out of character, he struggled. Though he dove into the role of “movie star,” Kristofferson was far too smart to fool himself into thinking he was a first-rate actor. At times, he seemed almost embarrassed to be in Hollywood blockbusters.

What none of us ignorant suburban kids understood at the time was that this was a man of great parts. A Rhodes scholar who trained to be an Army Ranger. A man who came within seconds of dying during that training when his chute got tangled on one of those jumps. He seemed to use that as a wake-up call. Kris Kristofferson turned down an offer to teach English at West Point – a job for which he seemed ideally suited – to pursue his great passion. He wanted to be a country songwriter.

He had neither the look nor the temperament for the job. And he sure didn’t have the connections. This is how he came to be 29 years old, with a wife and family, working as a janitor in Nashville.

The town, its history, and its people inspired him. He witnessed Bob Dylan slaving over lyrics at 4 a.m., alone in the studio. He knew how to fly a helicopter, and so he flew one out to Johnny Cash’s estate to deliver some lyrics to the great man himself. He tried whatever he could think of to break through. For a long time, none of it worked.

But eventually, people began listening to the early songs. The sharp listeners recognized that this scruffy young man, who was an average guitar player and had the kind of voice that only sounded good if you squinted, was writing the very best songs in a city of songwriters. And it wasn’t especially close.

Kristofferson was among the first country artists to manifest the schism that would explode in the world of country music in the early 1970s, and it remains in full force today. There was a traditional, conservative country that delivered love songs and heartbreak songs, often accompanied by highly professional session players, bathed in strings, swaddled in choirs, and sung by clean-cut, pure-voiced men and women.

And there was the younger, messier brand of country that was being created by progressive artists raised on rock & roll who neither looked nor sounded the part of a country star. Kristofferson was their poster child.

He wrote songs about having sex, about not having sex, and about getting drunk when you weren’t having sex. He wrote them with the attention to detail and sense of narrative that are the hallmarks of great authors. Kris Kristofferson was a scholar, and he knew the classics, whether it was William Blake or Hank Williams.

Nashville was afraid of those early songs – “Help Me Make it Through the Night,” “For the Good Times,” “Sunday Morning Coming Down,” and “The Law is For the Protection of the People.” They were too graphic, too adult, too political. Country radio wouldn’t play them. Country labels wouldn’t let their artists record them. But they got recorded anyway. They were just too good. Brave artists with enough clout put them out on record, and whether the label supported them or not, the country music listeners devoured them. This was adult music. This was music worthy of serious attention.

His biggest success as a songwriter came when he was challenged to write a song about the receptionist at Monumental Records, where he signed his first contract. Her name was Bobbie McKee. Kris changed one letter in the last name. Everyone wanted to record “Me and Bobbie McGee.”

His on-again/off-again girlfriend Janis Joplin did the definitive version shortly before her death. Kristofferson didn’t even hear that record until after Joplin was dead. The line “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose” would become one of the most evocative lyrics of a most turbulent era.

Kristofferson recorded all of his original compositions, but he was not a great singer. He knew it. Others had bigger hits with his songs. One of the many singers who recorded a song or two was Rita Coolidge, whom he would marry in 1973. Their recording of Kris’s “From the Bottle to the Bottom” won a Grammy in 1974. That’s around the time Hollywood came calling.

Kristofferson left Nashville around the same time Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings also moved along. But while Willie and Waylon spent much of their time in Austin, Kris moved to L.A. The drinking and womanizing that had been part of his life grew along with his movie star fame. It was just too easy. His songwriting suffered. His marriage ended.

Then, a decade later, he joined up with Willie, Waylon, and Johnny Cash to form one of the all-time musical supergroups – the Highwaymen. It was four veterans of the country music wars – four friends, four rivals. Four men who had been through a lot, both professionally and personally, and now were teaming up to have some fun. The conservative Jennings and the outspoken progressive Kristofferson were often on the verge of throwing punches at each other, but the underlying love and respect – along with a well-timed Willie Nelson quip – kept the friendship afloat.

Waylon once said about Kris, “He dresses like a bum, but, God, what a songwriter.” I got that quote from Brian Fairbanks' excellent 2024 book “Willie, Waylon, and the Boys.” I learned much of what I now know about Kristofferson – along with his Highwaymen cohorts – from that book. Fairbanks quotes Cash as saying, upon first hearing “Help Me Make it Through the Night,” “That man’s a poet. Pity he can’t sing.”

And he quotes Willie, now the last remaining Highwayman, as saying about Kris, “He shows more soul blowing his nose than the ordinary person does at his honeymoon dance.”

The common wisdom was that Kristofferson lost some of that soul after those early songs – songs that helped rewrite the very definition of what country music could be. That same wisdom says that the associations with Coolidge and the Highwaymen are what kept Kristofferson a presence in the music industry. There’s some truth to that.

But Kris Kristofferson didn’t just forget how to write brilliant songs. Nor did he stop caring passionately about vital issues. His defense of another outspoken musician, Sinead O’Connor, is probably what younger audiences are most familiar with today. He wrote it in 2009, decades after he was supposed to have stopped being a force in the world of music. A lot of songwriters would kill to write a chorus as pointed and sublime as this:

“And maybe she’s crazy and maybe she ain’t

But so was Picasso and so were the saints

And she’s never been partial to shackles or chains

She’s too old for breaking and too young to tame.”

It’s easy to see now that he’s gone that Kris Kristofferson, whether he knew it or not, wasn’t merely writing those words about Sinead O’Connor. He was writing them about himself.