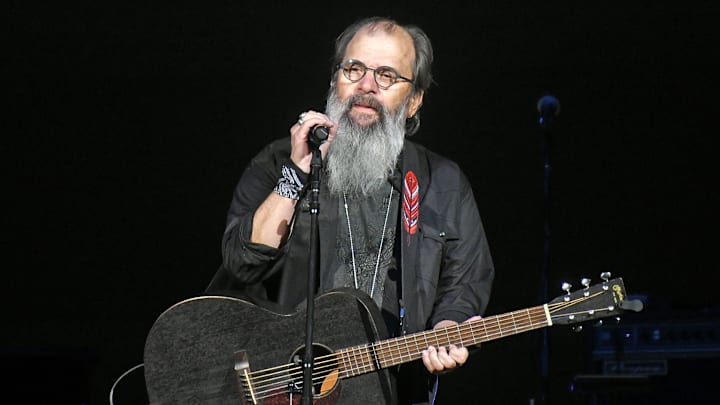

Steve Earle can’t tour as much as he used to. Age and familial obligations keep the 69-year-old off the road for all but about three months out of the year, quite a departure from his younger days. In his show Monday night at the Birchmere in Alexandria, Virginia, he explained to the sell-out crowd that the limited tour schedule means he doesn’t feel like he has to change his set list as often, because he’s not usually hitting the same towns in consecutive years.

But the Birchmere is special. It’s an iconic part of American music and one of the venues Earle plays whenever he can. Thus, he spent a good part of Monday’s set thinking of what he played last time and figuring out ways to change it up a little bit for his recurring fans. Being one of them, I certainly appreciated the effort.

Not that it matters all that much. Earle’s gruff voice and pronounced compassion for the little man are always engaging, regardless of which of his many excellent songs it is being paired with. He opened his set on Monday with the blues – the “Tennessee Blues” that is, from his 2007 album Washington Square Serenade, in which he literally says goodbye to Nashville, the city that launched him twenty years earlier. And he says hello to New York City, which has been his home ever since.

Steve Earle still knows how to entertain

Earle returned to the blues often on Monday. When you’ve lived his kind of life, battling and ultimately defeating serious addiction issues only to then watch his son Justin die from an overdose in 2020, the blues are never too far removed. As he noted before playing “South Nashville Blues” in the middle of his set, “This is the part of night where we start listing irretrievably to the blues, and when that happens, there’s f**k-all you can do about it.”

But this should not convince anyone that a Steve Earle show is a somber affair. With his larger-than-life persona and his deep well of passion for his subjects, it’s impossible not to get swept up in his music, whether you agree with his political stances or not. Only about half the crowd applauded his pro-union intro to “It’s About Blood,” from his COVID-abridged project about the Upper Big Branch mining catastrophe in West Virginia in 2010. But everyone sang along to the next number – “Harlem River Blues,” one of his son’s best songs, which Earle included on his tribute album a few years back.

And during 1995’s “Angel is the Devil” when he sang “Got the kind of face, you swear you seen someplace before – Well, it coulda been your mamma, or it coulda been a Mexican whore,” the people sitting next to me couldn’t stop laughing for the rest of the song.

Earle wears his political beliefs on his sleeve, which could get tiresome if it weren’t for the fact that he writes some of the best songs produced in America over the past forty years. So when he talks about the NRA or about Bill Maher’s disdain for religion, it may put some listeners off. But when he follows the statements up with brilliant songs like “The Devil’s Right Hand” or “God is God,” it’s hard not to buy a lot of what he’s selling.

“God is God,” whose simple message is that mortals should leave the divine stuff to the man upstairs and just try to live their lives as best they can, is the kind of song “you write when you’re pushing sixty,” Earle explained. It followed one of his earliest songs “Tom Ames' Prayer,” the kind of song “You write when you’re twenty.” One is about an outlaw trying to make a name for himself. The other is about acceptance of limitations.

Earle also paired “South Nashville Blues,” a song he wrote around the time he was getting sober, with “Cckmp,” (which stands for “cocaine cannot kill my pain”) written at the same time. He explained that he worried the first song may have made addiction sound like fun, so he always plays the darker side of it in tandem to remind everyone of its utter devastation.

Earle is a veritable repository of Americana. In addition to his 21 original albums, he has recorded four tributes. The first three were to his mentors – Townes Van Zandt, Guy Clark, and Jerry Jeff Walker. He told the story of how Jerry Jeff was the first person to take Jimmy Buffett to Key West, and how Earle saw Buffett for the last time at Jerry Jeff’s funeral. Then he played “Mr. Tambourine Man,” a Jerry Jeff song that Earle began performing when he was 14.

The final tribute album was to his son Justin Townes Earle.

There were plenty of hits to go around, from his first “Guitar Town,” to his biggest “Copperhead Road,” on which he traded his guitar for a mandolin. He also played the mandolin on the crowd-pleaser “Galway Girl.” And he played one of his songs that has particular relevance in the mid-Atlantic – “Taneytown,” a harrowing story of racial violence set in small-town Maryland.

Through the 22-song set, by himself on stage, with just a 6- or 12-string guitar, or mandolin, Steve Earle knows how to hold a crowd’s attention.

Opening the show was 20-year-old Richmond singer/songwriter Jack Wharff, who was clearly star-struck at playing such an iconic venue in support of such an iconic headliner. He kept repeating how unbelievable it all felt. Fortunately, any nervousness he may have experienced disappeared when he began singing.

His rough, high tenor recalls Neil Young, and he has the guitar chops and songwriting skills to continue the comparison. Wharff opened with a countrified version of Pink Floyd’s “Time,” because that’s the song he has been playing longest and feels most comfortable performing. Then he launched into a series of very strong originals, before playing his father’s favorite song, “John Hartford’s “Gentle on My Mind.” He closed his half-hour with a new song “Richmond City Jail,” which let him run wild on his guitar for a while.

Wharff may be the future of country music. Earle keeps its past alive, while still remaining very much in the present.