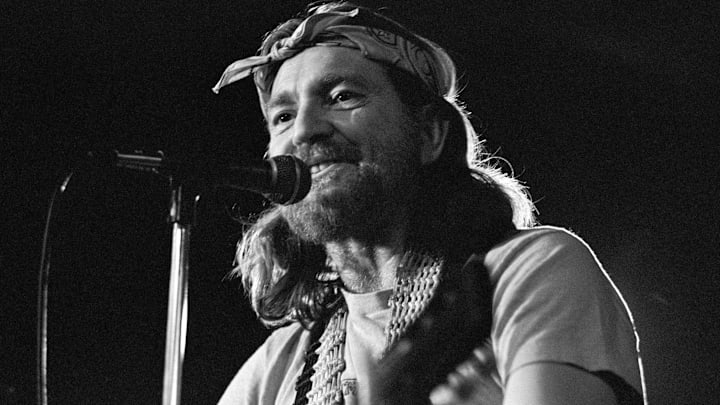

By 1973, Willie Nelson had released 15 country albums to modest results. Everyone recognized him as a top-flight songwriter, but as a performer? He wasn’t exactly standard issue Countrypolitan material. Kind of funny-looking. A thin voice. And though he had dutifully conformed to Nashville standards for much of his recording career, it is evident that there was something of a rebel inside.

He began letting that rebel out when he moved from RCA to Atlantic. First came Shotgun Willie, which blasted off his previous clean-cut image. Then, Phases and Stages, a concept album for which Willie abandoned Nashville altogether and recorded down in Muscle Shoals.

Both had moderate success, scoring about as well on the country charts as his final RCA albums had done. If anyone bothered to look, they might have noticed that both Atlantic albums also crept onto the very back end of the pop chart as well.

An iconic Willie Nelson album is about to reach a milestone

Atlantic didn’t care. They thought they were getting an established star to help them launch a foray into the country music scene. The two albums he recorded for them did not achieve that. Atlantic pulled the plug not just on Willie, but on their fledgling attempts to enter the country market.

Over at CBS/Columbia, they were paying attention. With the help of his good buddy Waylon Jennings, who had a string of country hits in the early ‘70s for RCA, Willie signed a new deal with Columbia that gave him complete artistic control. Then he went to Garland, Texas, to record his first album under his new contract.

Nelson said he chose Autumn Sound in Garland because it was remote, far away from any record company executives. He didn’t want Columbia’s interference. He didn’t want their seasoned studio musicians backing him. He didn’t want his new record to be polished and shiny.

Willie brought his touring band, the Family, up to Autumn and began recording. He had Micky Raphael playing harmonica. Paul English and his brother, Billy, played the drums. Bee Spears was on bass, and Jody Payne handled guitar and mandolin. Bucky Meadows played whatever was needed, including piano, which was otherwise handled by Willie’s sister Bobbie.

The songs they were playing constituted a bit of a departure even from Willie’s previous two albums. Like Shotgun Willie, the new album had a raw quality that felt unfinished. Like Phases and Stages, it followed a broad narrative scheme.

Phases was a concept album about the breakup of a marriage. The new material went even farther. Though also based on a relationship gone wrong, it traced the past, present, and future of a breakup, set in the Old West.

Willie wrote some new material for the album, but much of it was comprised of old-time country songs that Willie knew from his younger days. One of those songs, written by Carl Lutz and Edith Lindeman, told a tale of a lonely man, a lost love, and a murder. It was called “Red Headed Stranger,” and it gave the album its title.

Red Headed Stranger is comprised of 15 tracks, but only three of them run longer than three minutes. Several are shorter than 90 seconds, including a recurring “Time of the Preacher Theme” that shows up periodically to serve as a bridge between songs.

Nelson could say more in one minute than most songwriters could tell in five. The second side of Red Headed Stranger kicks off with one of those short Nelson originals – “Denver.” It captures the lonely longing that pervades the entire album and tells a complete story in just 53 seconds.

And Willie didn’t need lyrics to convey that precious sadness, as he shows on the album’s closing track “Bandera.” The lovely coda shifts between Raphael’s mournful harmonica, Bobbie’s lilting piano, and Payne’s guitar and mandolin runs. It plays as a closing credits theme to a movie about the Old West that did not yet exist. (A film would eventually come some ten years later, starring Willie no less. You’re better off sticking to the album.)

Nothing about Red Headed Stranger predicted a hit. Columbia execs were appalled when they first heard it. It sounded like a demo. It sounded like it had been slapped together in one take and never finished or mixed properly.

It sounded like that because that’s precisely what it was. Nelson and his band essentially recorded the entire thing in a single day. They spent a few more days cleaning up obvious mistakes and mixing, but Willie insisted that his voice not be tampered with.

He wanted it to sound raw and rough. It didn’t seem to fit into either of the country’s two poles. It certainly wasn’t countrypolitan. There wasn’t a violin or backing chorus in sight. Nor was it the rock-tinged outlaw country that Columbia was probably expecting.

Worst of all – to the execs, at least – there was no hit. Just a lot of songs that were too old to remember and some new Nelson-penned material that seemed to serve as transitional filler. What they didn’t see – or hear – was an old song written by Fred Rose that had been a hit almost thirty years earlier.

What they missed was “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain.”

The simple, gentle take on heartbreak comes midway through the first side, built on a plaintive guitar figure and harmonica. Willie’s sweet, honest delivery took off. A radio station started playing it, and the audience loved it.

“Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” didn’t just become a hit. Willie had plenty of hits on the country charts before 1975. But he never had a number one. Until “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain.” It was the number one country song for the entire year.

And more importantly, it crossed over, hitting 21 on the pop chart. Willie had never tasted the pop chart before then. This would not be the last time he’d get there.

Red Headed Stranger had plenty more to offer. Another old song, “Remember Me,” also became a significant hit. A spare version of Jeannie Seely’s hit “Can I Sleep in Your Arms” shows off how expressive the Family could be when they kept things simple. It borders on gospel. The aforementioned “Denver” is one of the great under-one-minute songs you will encounter.

Columbia reluctantly agreed to release Red Headed Stranger with little fanfare. Willie had the contract on his side, and they figured the album would flop and their star would return to recording the kind of albums they wanted.

It didn’t tank. It went to number one on the country chart – Willie’s first time there. His two albums for Atlantic had charted on the pop chart but never climbed above the top 100. Red Headed Stranger hit 28. It was the first of 13 number-one country albums Willie Nelson would release in the ensuing decades, along with a dozen more top tens.

In some ways, Red Headed Stranger is to country music what Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska is to rock & roll. Both were spare visions, recording quickly and cheaply. Both emphasized authenticity and sharp songwriting over pretty effects and walls of sound.

The only real difference is that whereas Nebraska influenced countless musicians across multiple genres, Red Headed Stranger became a massive hit. It didn’t merely influence country artists. It influenced country music executives, and in doing so, helped change the course of Willie Nelson’s career and the country music genre.