Want to start a fight with a late Baby Boomer, born sometime around 1960? Tell them that Steely Dan’s 1977 album Aja is an overrated collection of perfectly crafted, mostly boring jazz-pop pretension. For some reason, late ‘70s FM radio bought into the hype and Aja became known as their greatest achievement.

Never mind that the hits like “Peg” and “Deacon Blues” function better as insomnia aids than as pop songs. The album took Donald Fagen and Walter Becker’s penchant for relying on studio musicians and meticulous engineering to its extreme, and in the process squashed whatever might have been alive in the songs.

If that sounds harsh, good. That was my intention. However, I do not come here today to bury Steely Dan. I come to praise. There is no need to inflate Aja’s reputation. That’s because several years before the five-minute “Black Cow” kicked off Aja, Fagen and Becker had already produced one the greatest albums of the 1970s – indeed, one of the best American pop albums of the latter half of the 20th century. In 1974, Steely Dan released Pretzel Logic.

Steely Dan produced one of their best albums 50 years ago

Pretzel Logic, which turns fifty on Tuesday, offered eleven songs in a tight 34 minutes. It boasted Fagen and Becker’s caustic wit when looking at the ugliness in the world, and their sad-but-hopeful take on love. Best of all, it offered the best blend of jazz rhythms with SD’s penchant for pop hooks that the duo would ever achieve. Its weakest tracks are pretty good, and its best songs, which account for at least half the tracks, are brilliant.

Pretzel Logic came after the failure of SD’s second album, Countdown to Ecstasy. That album had a number of wonderful songs, led by the glorious name-dropping “Show Biz Kids,” and it went over well with critics. But to the public, eager for more songs like “Do It Again” and “Reelin’ in the Years” from the debut album, this sophomore effort came across as a minor letdown. That reaction led Fagen and Becker to two crucial decisions.

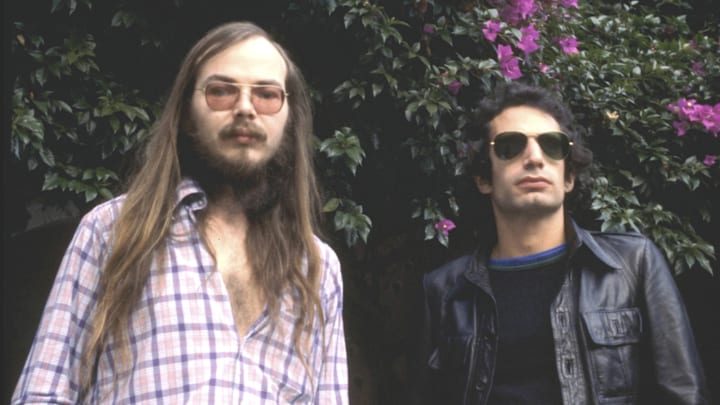

First, they decided that they did not like touring and essentially became a studio band from that point forward. This decision, along with a desire to maintain ever-stricter creative control over the band’s output, also led Fagen and Becker to cut ties with the rest of the original lineup, most notably guitarists Denny Dias and Jeff “Skunk” Baxter. Dias, Baxter, and original drummer Jim Hodder would all play on some of Pretzel Logic, but they served more as session players than as full members of the band. This would establish the pattern Fagen and Becker would embrace for the rest of their glory years. They were a two-man, studio-bound operation, bringing in first-rate session players as needed.

Their second decision involved the songs they would record. Whereas six of Countdown to Ecstasy’s eight tracks ran longer than five minutes, nothing on Pretzel Logic would approach that. More than half the songs on the third album ran under three minutes. This was crucial for idiosyncratic musicians like Fagen and Becker, who were prone to go off on directionless tangents if they didn’t remain disciplined. Though they could absolutely hold a listener’s interest on some of their longer jazz excursions, they benefitted quite a bit from putting some reins on those impulses.

It all came together perfectly on Pretzel Logic. From session pianist Michael Omartian’s syncopated chords that open the lead track “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number," the jazzy innovations are all there. But they are balanced by the gorgeous pop sensibilities of “Any Major Dude” a few tracks later. Becker’s guitar is constantly adding offbeat runs, along with similar contributions from both Baxter and Dias, as well as from Dean Parks (who would return a few years later to play the iconic guitar on SD’s song “Haitian Divorce). There are horns and keyboards throughout.

All of this instrumentation comes together to close out side one with an excellent take on Duke Ellington’s instrumental “East St. Louis Toodle-Oo.” Becker takes the lead with his voice-box guitar, while Fagen plays sax and Baxter contributes some steel guitar.

Then, on side two, Fagen and Becker hit their songwriting peak. The first and last track on side two – “Parker’s Band” and “Monkey in Your Soul,” are decent songs. The four tracks sandwiched in between are all gems. There’s the high drama of “Through with Buzz,” seemingly announcing the band’s new, more personal direction. There’s the haunting, mysterious title track, which features some of Fagen’s best singing to date. There’s mini-epic “With a Gun,” an entire Western film in 140 seconds. And there is one of the duo’s most poignant tracks – the galloping story of an addict’s overdose, called “Charlie Freak.”

The track with most lasting significance may be the deceptively breezy “Barrytown” from side one. Interpretations of the song’s actual subject have varied over the years. The Rev. Sun Myung Moon purchased land for his Unification Church near Bard College, where Becker and Fagen were both students, around the time they were working on the album. The church was built a few years after the duo had dropped out and moved to LA, but the lyrics of the songs seem to fit with the culture clash the “Moonies” engendered along the Hudson River in the mid-‘70s. In fact, those lyrics ring as true today as they did in 1974.

“I’m not one to look behind, I know that times must change – But over there in Barrytown, they do things very strange – And though you’re not my enemy, I like things like they used to be, and though you’d like some company, I’m standing by myself – Go play with someone else – I can see by what you carry that you come from Barrytown.”

I had the privilege of seeing a rare Steely Dan live show before they stopped touring. It was 1973. I was eleven. They were opening for Cheech and Chong at the Shady Grove Music Fair in Gaithersburg, MD, a modern, stucco-studded theater-in-the-round. Tickets were $6.50. I didn’t know much about them, but I loved “Reelin’ in the Years” and still remember them playing it.

I’m a little bit sad they stopped touring and I never got to see them again, but if it was what it took to get to Pretzel Logic, as well as follow-ups Katy Lied and The Royal Scam, I can forgive them. I can even forgive them for Aja. If another band had done it, I probably would have been a fan. But not the band that did Pretzel Logic. They were better than that.